Back at the end of March, when Ralph Drollinger pronounced that homosexuals and environmentalists were to blame for COVID-19, I rolled my eyes and mostly ignored it. Sure, it’s frustrating that this sort of thing is still tolerated by cabinet-level members of the US government, but mostly it was frustrating that his relationship to public officials gave a megaphone to a belief that is widely but less publicly held by many Christians across the country. The position itself was not new information, and now (more than ever) I don’t have shock and outrage to spare for it.

In the last week, though, I was asked to help edit a friend’s formal reply to Drollinger, and it gave me a more complete picture of the argument he was making as well as pointed me toward some new insights that are consistent with previous thoughts posted here. So, in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of Earth Day, I wanted to offer my own response to Drollinger’s screed, particularly as it regards environmentalism.

Drollinger’s study at the end of March actually had relatively little to say about environmentalism, beyond that “mankind is separate, special and superior as it relates to all God has made” and that therefore anything that would make man “subservient” to non-human creation is sinful and meriting judgement (consequential or otherwise). He then directs readers to a fuller study of the issue from April of 2018. Here Drollinger reiterates and elaborates on his points, specifically focusing on the ideas that (A) belief in anthropogenic global warming represents an arrogant usurpation of the divine power of creation and (B) environmentalism inverts the true hierarchy of the world by elevating non-human creation above its station.

In both entries, Drollinger declares (citing Romans 1) that the problem is “when humans inappropriately exalt His creation and worship it at His expense.” Perhaps there are some somewhere who do worship creation rather than the creator, but this argument is largely a straw man. Christian environmentalists don’t worship nature at God’s expense; they defend the environment as a form of service to God (as the “stewards” of earth, an idea that Drollinger leans on heavily). More importantly–and this is what the response I was editing helped me realize–this isn’t actually Drollinger’s concern. He makes a great show of fretting that creation is being placed ahead of God in the cosmic hierarchy, but his real outrage is that non-human creatures might be placed ahead of humans.

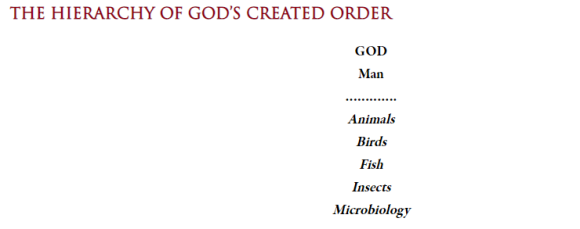

Hammering over and over the text of Genesis 1, Drollinger insists that the imago dei means that human beings are not just different from creation but “superior” to it in an almost godlike way. The image and likeness of God “carry the idea of man being a reflection or similitude of God’s communicable attributes and characteristics.” This not only gives us the power to “rule” and “subdue” creation, but places us in a categorically different cosmic realm than the rest of God’s creation. Drollinger includes a nifty chart to help you visualize this:

Not only are we humans placed right under God, but there is a convenient line indicating that we are, taxanomically, of the God order of things and not the creatures order of things. It’s hard to avoid the perception that the whole argument boils down a deep insecurity from Drollinger that his own honor might be diminished if he were to sacrifice his wants, desires, or even needs for anything other than God Himself.

Drollinger, and the particular type of Christian anti-environmentalist he represents, have failed to internalize the story of Mark 9—or really of the Gospels in their entirety.

And they came to Capernaum. And when he was in the house he asked them, “What were you discussing on the way?” But they kept silent, for on the way they had argued with one another about who was the greatest. And he sat down and called the twelve. And he said to them, “If anyone would be first, he must be last of all and servant of all.”

The disciples were not so unlike Drollinger as they walked along the road, quietly trying to create hierarchies of greatness. Who is superior, who would be put under who else’s feet? The key difference between Drollinger and the disciples is that they had the good sense to be ashamed of what they were saying. They knew intuitively that jockeying for position was inconsistent with the message of Jesus. Jesus makes sure to explain why: those who follow him must become servants. After all, this is the essence of the gospel, that the Son did not consider equality with the Father something to grasp and so emptied himself for beings infinitely smaller, weaker, lesser than he was.

Increasingly, Matthew 25.40 (“Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.”) is being deployed as an eco-text, and while non-human creation seems to stretch well beyond the author’s intent here, the principle expressed is justly applied to Christian environmentalism. After all, to both take Jesus as our exemplar and to refuse to extend our spirit of charity and self-sacrifice to non-human creation is to claim implicitly that the distance between ourselves and a God who sacrificed himself for us is somehow less significant than the gap between human creatures and non-human creatures. That may be, in fact, what Drollinger believes—that we are much farther above the rest of creation than God is over us—touting as he does the imago dei as a universe-defining characteristic of humanity. (It does, though, seem to run very much contrary to his feigned frustration over the “ultra-hubristic” nature of environmentalism.)

In the end, Drollinger makes the same fundamental mistake that so many of us do, focusing on what we are allowed to do instead of what we can give up. Perhaps Drollinger is right that humanity is distinct from the rest of creation in a way comparable to the way God is distinct from us. I certainly do not want to downplay the significance of the imago dei. In fact, I would appeal to just that image of God in us to defend environmentalism. I am made in the image of God who sacrificed himself when he was under no obligation to, who gave up his very life as a pure act of love and out of reverence for the Father. Instead of worrying about how great I am compared to the rest of creation, I want to be like the God in whose image I am made and ask myself, how can I serve this creation. Not out of reverence toward or worship of creation but out of reverence toward and worship of God, who made this creation and entrusted me with its care. It is precisely because we are “lords” of creation that we can and should serve it rather than ourselves. That’s the message of the gospel. I hope Drollinger and others have ears to hear it.

Mark Fiege’s Republic of Nature is a work of sufficient size and importance to warrant a full review of its contents. William Cronon, rock star of the environmental history world, offered significantly more effusive praise in his foreword: “It is surely among the most important works of environmental history published since the field was founded four or more decades ago. No book before it has so compellingly demonstrated the value of applying environmental perspectives to historical events that at first glance may seem to have little to do with “nature” or “the environment.” No one who cares about he American past can ignore what Fiege has to say.” Nor should they. Fiege’s work–which takes nine standard topics in American history and refashions them to include environmental history–demands engagement from scholars and its easy style invites it from the general public. Necessarily, a work which is linked by a common methodology rather than a common chronology or theme will be somewhat uneven, but Fiege succeeds more often than he fails in challenging the standard historiography and revolutionizing the way environmental history applies to more “conventional” history. But, as much as Fiege’s work demands full engagement, a particular chapter has so seized my attention as to compel me to stop the general review there and turn to a more particular issue: the development of the atomic bomb and Fiege’s attempts to justify it or, at the very least, mitigate the responsibility of the scientists involved.

Mark Fiege’s Republic of Nature is a work of sufficient size and importance to warrant a full review of its contents. William Cronon, rock star of the environmental history world, offered significantly more effusive praise in his foreword: “It is surely among the most important works of environmental history published since the field was founded four or more decades ago. No book before it has so compellingly demonstrated the value of applying environmental perspectives to historical events that at first glance may seem to have little to do with “nature” or “the environment.” No one who cares about he American past can ignore what Fiege has to say.” Nor should they. Fiege’s work–which takes nine standard topics in American history and refashions them to include environmental history–demands engagement from scholars and its easy style invites it from the general public. Necessarily, a work which is linked by a common methodology rather than a common chronology or theme will be somewhat uneven, but Fiege succeeds more often than he fails in challenging the standard historiography and revolutionizing the way environmental history applies to more “conventional” history. But, as much as Fiege’s work demands full engagement, a particular chapter has so seized my attention as to compel me to stop the general review there and turn to a more particular issue: the development of the atomic bomb and Fiege’s attempts to justify it or, at the very least, mitigate the responsibility of the scientists involved. society open to allow a utopian global community. The description would be comic had Fiege intended it as a farce, but he truly believes that the scientists, through purely humanitarian motives, were compelled to create the most destructive weapon in human history. Never mind that anyone with a high school level grasp of history could have easily demonstrated that bigger weapons make for bigger wars, not peace. The scientists, as the day of completion drew nearer, began to have these same realizations but, rather than abandoning the project, instead convinced themselves that a benign demonstration of its power would be sufficient to establish their idyllic society.

society open to allow a utopian global community. The description would be comic had Fiege intended it as a farce, but he truly believes that the scientists, through purely humanitarian motives, were compelled to create the most destructive weapon in human history. Never mind that anyone with a high school level grasp of history could have easily demonstrated that bigger weapons make for bigger wars, not peace. The scientists, as the day of completion drew nearer, began to have these same realizations but, rather than abandoning the project, instead convinced themselves that a benign demonstration of its power would be sufficient to establish their idyllic society. It was a beautiful and thorough deception, no doubt, but it was still false and ultimately incomplete. The scientists, history remembers, went on to regret their mistake, to see the atomic bomb for what it really was. A horror, both in principle and in its tragic application in Japan. An enormity of the modern mind that is without justification and without legitimate purpose. That this realization hit only when the war was over and a cessation of hostilities (but by no means peace) was won demonstrates the true root of the scientists motives. They were engaged in an epic struggle for nation or, if you prefer, self-preservation. They were not, as Fiege concluded, pursuing the good, the beautiful, the true with an innocent curiosity and in a context of “openness, toleration, and democracy.”* As much as Fiege may wish it were so, the heart of war is not “deep moral ambiguity” and the scientists are not absolved by their good intentions. In fact, Fiege neglects to entertain the seemingly logical conclusion that they had no such benign intentions, only convincing rationalizations. It is in the clear distinction between motives and justifications that Fiege’s interpretation flounders.

It was a beautiful and thorough deception, no doubt, but it was still false and ultimately incomplete. The scientists, history remembers, went on to regret their mistake, to see the atomic bomb for what it really was. A horror, both in principle and in its tragic application in Japan. An enormity of the modern mind that is without justification and without legitimate purpose. That this realization hit only when the war was over and a cessation of hostilities (but by no means peace) was won demonstrates the true root of the scientists motives. They were engaged in an epic struggle for nation or, if you prefer, self-preservation. They were not, as Fiege concluded, pursuing the good, the beautiful, the true with an innocent curiosity and in a context of “openness, toleration, and democracy.”* As much as Fiege may wish it were so, the heart of war is not “deep moral ambiguity” and the scientists are not absolved by their good intentions. In fact, Fiege neglects to entertain the seemingly logical conclusion that they had no such benign intentions, only convincing rationalizations. It is in the clear distinction between motives and justifications that Fiege’s interpretation flounders.